Early-ballot stickers for voters in Pima County.

Early-ballot stickers for voters in Pima County.

Myth of monolithic voters

Political campaigns often target specific voter groups — like women, Latinos or Catholics. In the last couple weeks the Trump campaign has held rallies in Arizona branded as "Native Americans for Trump" and "Latter-day Saints for Trump." Meanwhile, the Biden campaign has launched Spanish-language ads and met with all the same groups.

But how uniform are the beliefs of voters within an assumed demographic?

University of Arizona political science professor Samara Klar said that actual monolithic voting blocs are pretty much exclusive to political parties.

"I think the only monoliths we could try to think about are Democrats and Republicans,” Klar said. “Democrats almost exclusively vote for Democratic candidates, Republicans almost exclusively vote for Republican candidates. But any demographic group that you're talking about, be it women or Latino voters, these are very bipartisan groups."

Latinos are expected to make up 13% of the national electorate this year. But Latinos are not a monolith, and they’re not the only group that gets treated like one.

In September, the group Living United for Change in Arizona, or LUCHA, launched a sweeping get-out-the-vote campaign to reach more than 1 million Black, Indigenous and Latino voters across the state. The political action group is focused on immigration and workers’ rights.

Alejandra Gomez, LUCHA’s co-executive director, said that’s a pool of potential voters who have been historically pushed to the wayside.

Latinos are expected to make up 13% of the national electorate this year. But Latinos are not a monolith, and they’re not the only group that gets treated like one.

Latinos are expected to make up 13% of the national electorate this year. But Latinos are not a monolith, and they’re not the only group that gets treated like one.

This year Arizona is a battleground state where both presidential campaigns are focused on those groups. President Trump and former Vice President Joe Biden have visited in recent weeks.

Gomez said there’s still a lot the campaigns are missing.

“Not only do we get treated as a monolith, but then we also get treated as a community that doesn’t care about elections, when that’s just not true,” Gomez said. “We have these conversations at the kitchen table, and the follow-up question is, ‘Where do I go vote?’”

This year LUCHA is campaigning for Biden. They have always supported progressive politicians in Arizona and nationwide.

But that’s not the case with other Latino campaigners.

Yasser Sanchez is a Mexican-American immigration attorney and longtime Republican in Mesa. He campaigned for Mitt Romney in 2007 and John McCain’s last run in 2018.

Since taking office, Trump has tried to cancel policies like the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program, which protects some undocumented immigrants brought to the U.S. as children. Trump also enacted family separation policies and sweeping changes to asylum. Sanchez felt like he couldn’t recognize the Republican party anymore.

Now, for the first time in his political career, he’s campaigning for a Democrat: Biden.

Sanchez says although the Trump administration has hosted several Latino-focused campaign rallies, he does not believe he’ll win Arizona.

Latinos here are largely of Mexican origin, a demographic some polls have shown increasingly support Biden. But a recent Pew study found Cuban Americans remain mostly Republican.

Another group increasingly targeted by political campaigns are Indigenous voters. The state is home to 22 recognized tribes. This year Indigenous people make up 6% of Arizona's electorate — a percentage experts say could have significant sway. Tribal members are also on the ballot.

Native Americans in Arizona gained the right to vote in 1948, but like many nonwhite voters, the ability to easily exercise the right to vote didn't come till the 1960s with the signing of the Voting Rights Act. It wasn't till 1970 that literacy tests were banned.

Rosemary Avila works with All Voting is Local, an advocacy group that tries to break down discriminatory voting barriers.

She said a real barrier that remains to voting within Arizona tribal lands is the lack of post offices, with only 48 covering almost 20 million acres. Since rural reservations don't usually have street addresses, many rely on post offices for mail-in ballots, but this still can require traveling hours to vote.

"All of these things have a cumulative effect. It has impacted Native Americans' turnout and their ability to participate in our democratic process,” Avila said.

A screenshot from a Facebook Live video voting advocates hosted Sept. 28, 2020, to answer Native American Arizonans' questions about voting.

A screenshot from a Facebook Live video voting advocates hosted Sept. 28, 2020, to answer Native American Arizonans' questions about voting.

For years there has been talk about the Evangelical vote and the Catholic vote. And in Arizona there is discussion of the Latter-day Saints, or Mormon, vote. But grouping voters based solely on their faith is not that simple.

Rachael Clawson lives in the metro Phoenix area and is involved with campaign groups for Biden and Harris. She is part of a growing number of members of the LDS church who admit they are breaking from what most people assume is a solid Republican block of voters.

“It’s becoming more normal for Latter-day Saints to be either registered Independents or registered Democrats,” Clawson said.

Other major religious groups across the country also are not uniform when it comes to how they vote. Greg Smith with the Pew Research Center said there is a large fissure within the Catholic Church, a group that represents many people of faith in Arizona and makes up the second -largest group of Christians in the U.S.

“The Catholic population in the United States is deeply polarized along partisan lines just like the population as a whole,” Smith said.

Pew research shows that the political split within the Catholic Church also breaks down along racial lines. White Catholics tend to be Republican and nonwhite Catholics tend to be Democrats. Smith said that trend holds true for most American Christians, with exceptions.

When it comes to religion and politics, Chris Weber, a political scientist at the UA, said partisanship is less a matter of identifying with a particular religious group and more a matter of beliefs.

“If we’re thinking about religion, one of the strongest predictors of voting isn’t really affiliation or denomination, it's a belief in religious orthodoxy and tradition,” Weber said.

Religious voters do represent a large share of the nation's electorate. But in the most recent Pew Religious Landscape Survey, the percentage of voters who identify as having no official religion, including agnostics and atheists, represent about 23%. That number is larger than the percentage of Catholic voters and rivals the percentage of Evangelical protestants.

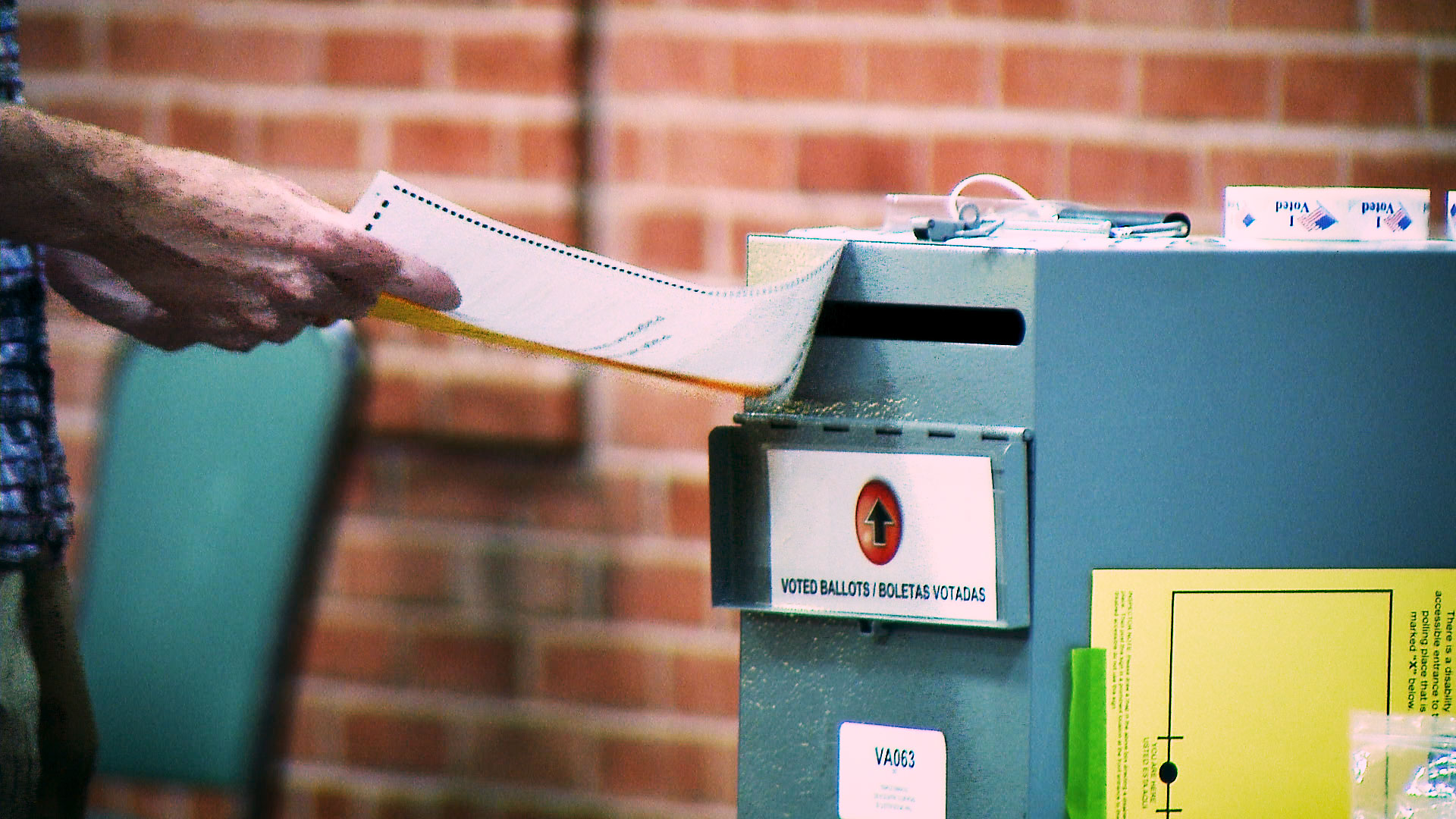

A voter turns in his ballot at a polling site set up at Tucson's Temple Emanu-El on the day of Arizona's primary election, Aug. 4, 2020.

A voter turns in his ballot at a polling site set up at Tucson's Temple Emanu-El on the day of Arizona's primary election, Aug. 4, 2020.

Perhaps the largest voting bloc targeted by campaigns is women. Representing half of the population, it's clear that this group is not a monolith, even though it is often treated as one. University of Arizona political science professor Samara Klar said women are very divided along partisan lines.

"Nonwhite women are overwhelmingly supportive of the Democratic Party, but white women have supported the Republican Party in every presidential election in recent memory,” Klar said. “So there's a lot of divides within this group we call the 'female voting bloc.' It really doesn't exist."

Having a female candidate on the ticket also does not overwhelmingly spur women to support one party over the other, as the country saw in the 2016 election.

Even so-called “women’s issues” like reproductive rights divide women along party lines. Klar said the issue that most women might be united on in this election would be the economy, as women have left the workforce at a much higher rate than men since the start of the pandemic.

By submitting your comments, you hereby give AZPM the right to post your comments and potentially use them in any other form of media operated by this institution.