In the classic Hollywood film, the West was more of an imaginary place than an historical location. A lot of the actual history took place in what we now call the Midwest and the Great Plains, but most Western movies, through a combination of convenience and aesthetic shorthand, seemed to occur in the Southwest deserts or canyon lands—and often both.

Listen:

If a story took place in Arizona, it didn’t necessarily look any different than all the other westerns that were quickly shot in the hills of southern California. Most Americans still lived in the East, so to the average movie-goer, Dodge City, Abilene, and Tombstone, may as well have been right next door to each other. It was all the same place, really—Hollywood.

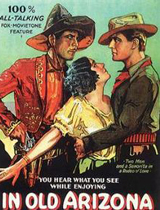

The first Western of the sound era, as it happens, was called In Old Arizona, made in 1928. The story took the Cisco Kid, an outlaw character created by O. Henry, and turned him into a charming anti-hero.

Raoul Walsh, already one of the top filmmakers in the business, took his crew out to Zion National Park and Bryce Canyon in Utah, and shot most of the picture with himself starring as the Kid.

They were driving back to California at night, with the intent of shooting some interiors at the Fox Studio, when—and I’m not making this up—a scared jack-rabbit bounded onto the windshield of Walsh’s car, shattering it, and a piece of glass injured the director, who ended up losing his right eye. He wore an eye patch the rest of his life, and apparently enjoyed the impression it made.

Anyway, the film was given to Irving Cummings, and most of it was reshot, with Warner Baxter, a popular romantic lead from the silent era, playing the Cisco Kid. It’s a curious little movie.

The Kid is a romantic Mexican bandit, apparently with some moral values: he robs the strong box from a stagecoach but refuses to steal anything from the passengers. He is in love with Tonia Maria, played by Dorothy Burgess, a shallow beauty who cares more about money than the Kid.

Along comes an army sergeant named Mickey Dunn, played by Edmund Lowe, who’s tasked with tracking the Kid down and capturing him, and he decides to seduce Tonia in order to do it.

Warner Baxter received a Best Actor Oscar for his performance in "In Old Arizona" (1928)

Warner Baxter received a Best Actor Oscar for his performance in "In Old Arizona" (1928)

Baxter does quite well imitating a Mexican, which is more than I can say for Burgess. Lowe’s phony Brooklyn accent is painfully bad, as well as anachronistic for the time period. Baxter sings a nice ballad, My Tonia, which started the tradition of the singing cowboy in movies, and the film quite obviously showcases the use of sound for its own sake in various effects, musical and otherwise.

Some of the outdoor footage from Utah survives, but most of the film appears to have been shot on a sound stage, and it has a slow pace and sometimes exaggerated acting style which seems dated today. But it sure impressed the film industry at the time, receiving four Academy Award nominations, including best picture and director, and with Warner Baxer winning the award for Best Actor.

Now, this was only the second year of the awards—they weren’t even called the Oscars yet—so they didn’t have the fame and prestige that came later. Still, it’s strange that what seems now such a minor performance—although not a bad one, mind you—would win top honors. As for Arizona, it’s in the title of the film, and that’s really about it.

There is one other, and considerably better, Arizona western from the classic era, that is actually about Tucson, sort of—and it’s called (surprise!) Arizona.

Released by Columbia in 1940 and directed by Wesley Ruggles, the picture stars Jean Arthur as a tough pioneer woman in the 1860s in Tucson who wants to start a freight business but runs up against corrupt competitors.

Along comes William Holden as a freedom-loving cowboy who later joins the cavalry, and of course she takes a liking to him. Warren William is the villain, and the plot manages to include Apache Indians, stampeding cattle, the Civil War, and a lot of other classic western situations.

Supposedly the 39-year-old Arthur was worried that the 21-year-old Holden, (this was well before his breakthrough as a star) was too young for her—but she needn’t have. Their chemistry together is great. The film is fairly well-written, not in the top tier of great films by any means, but absorbing.

There’s an excellent bit towards the end where instead of showing us the climactic shoot-out, we only hear the gunshots from the perspective of other characters anxiously awaiting the outcome. But the thing that really struck me about the movie is how dirty and grimy everything looks.

In the opening sequence, for instance, when Holden enters Tucson with a wagon train, we are shown a squalid succession of huts, mostly poor Indians, and it’s really like you’d imagine Tucson might have looked then.

Throughout the film there is a vivid impression of dust, sweat, mud, and general lack of bathing that give us a more realistic version of the West, despite the conventional good guys-bad guys plot—and for that I give credit to the director Ruggles, an underrated figure in Hollywood history.

The picture was shot in Tucson, with some scenes in Sabino Canyon, but most of the sets were built to the west of town, on the site of what eventually became Old Tucson Studios. In fact, a few of the buildings from the film are still standing.

Arizona premiered here in 1940 at five theaters simultaneously, including the Rialto, the Fox, and the Temple of Music and Art—all of them sold out, with Jean Arthur and William Holden appearing in person, and the evening’s celebrations featuring a horse-drawn parade and a midnight feast with three thousand guests.

It was the first and last major Hollywood premiere to be held in the Old Pueblo.

For Arizona Spotlight, this is Chris Dashiell.

Who is Chris Dashiell?

Film reviewer Chris Dashiell

Film reviewer Chris Dashiell

Chris Dashiell has been writing about movies for seventeen years, serving as the editor of the online film lovers' guide Cinescene for ten of them. He currently reviews films for Flicks, a weekly program on Tucson's community radio station KXCI, and he confesses to shamelessly idolizing Carl Dreyer, Jean Renoir, and Luchino Visconti.

By submitting your comments, you hereby give AZPM the right to post your comments and potentially use them in any other form of media operated by this institution.