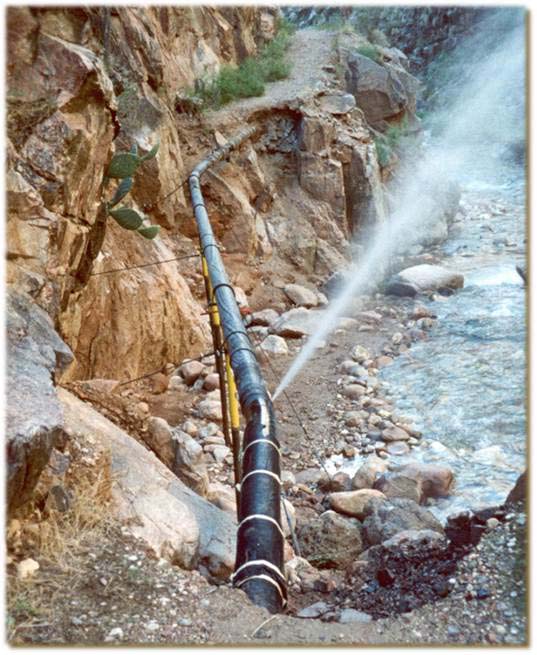

Building the original Transcanyon Pipeline in the Grand Canyon in 1965.

Building the original Transcanyon Pipeline in the Grand Canyon in 1965. Season 2 Episode 8: An unprecedented pipeline in an unprecedented place

This episode of Tapped was supported by a grant from The Water Desk, an independent journalism initiative based at the University of Colorado Boulder's Center for Environmental Journalism.

Episode transcription

Zac Ziegler: Let's start this episode with a bit of a trip back in the wayback machine. And no, I don't mean the website archive.org, I mean something more akin to the old Peabody's Improbable History bit from the Rocky and Bullwinkle cartoons.

(Cartoon music fades in. Once again, it is time to take another revealing peak back into history. What famous date should I set it to?)

A bit of context, I'm an alum of Northern Arizona University. For those who are unfamiliar, NAU's main campus is in Flagstaff, about a 90-minute drive from Grand Canyon National Park's main visitor center at the south rim.

ZZ: When you're an aspiring radio student at KJACK, NAU's college radio station who thinks news may be in your future, you consider that park a part of your coverage area.

So, today, I dug into a box of old electronics, found an external hard-drive old enough that it requires a separate power cable and a USB cable. I plugged it in and started searching.

Luckily for you and me, there is no audio of what I was searching for, so you don't have to hear me as I learned to read news on the air.

But there is a 17-ish year old script, with a reference to an issue with the 12-and-a-half-mile pipeline that supplies water to a portion of the national park, which hosts millions of visitors a year, not to mention the 2,000 people who work in the park and their families.

It says the pipeline was built in the '60s and is a few years beyond its planned life.

Little did I know that I could reuse portions of that script in newscasts from then until, really, today.

This is Tapped, a podcast about water. I'm Zac Ziegler.

Since 2010, there have been more than 85 major breaks that have disrupted water delivery. The breaks are expensive to repair, often exceeding $25,000. And they often happen in areas that are dangerous to repair, with access only by trail or helicopter.

But the pipeline is finally getting an upgrade, in what experts are calling an unprecedented undertaking.

It will involve crews repelling down cliff sides, helicopters flying in materials, dangerously high water pressure, and navigating not just unpredictable weather but also dramatically different weather in different parts of the canyon all while trying to accommodate the hikers, visitors and staff who make their living leading tours in the canyon.

Theme ends

When AZPM reporter Danyelle Khmara first started working on this episode, she didn’t even realize the Grand Canyon had a waterline. I mean, she had been there and she drank water, but where that water came from was not even an afterthought.

But over the last couple of months researching for this episode, she's learned that it’s going to be a project like no other and a story worth telling.

Danyelle takes it from here.

Building the original Transcanyon Pipeline in the Grand Canyon in 1965. Photos courtesy of Grand Canyon National Park

Building the original Transcanyon Pipeline in the Grand Canyon in 1965. Photos courtesy of Grand Canyon National ParkDanyelle: The Transcanyon Waterline has been plagued by breaks since the beginning. First built in 1965, around 40% of it was quickly destroyed by a 15-inch rainfall.

Crews had built the $2 million pipeline project in a creek bottom in Bright Angel Canyon, below the South Rim.

Crews began a $5 million project to replace the demolished waterline in 1967, but rather than in a creek bed, they built it higher in the canyon to keep it from flood waters. The insurance company at the time estimated that a dozen people would die during the construction. In the end, it was five.

Although the Colorado River runs through the Grand Canyon, its distribution had already been apportioned by the time there were enough people visiting the canyon to need the more robust water source.

And so crews built the pipeline to carry water from Roaring Springs, which still supplies the Grand Canyon with water today, to the Havasupai Gardens pump station, formerly known as Indian Garden, and then up to the South Rim.

The pipeline began running in 1970.

Building the original Transcanyon Pipeline in the Grand Canyon in 1965.

Building the original Transcanyon Pipeline in the Grand Canyon in 1965. Rob Parrish with the National Parks Service is in charge of the new pipeline project.

RP: We know that basically, right after it was installed, there was a thousand-year rainstorm that caused a huge flood in the canyon and wiped out a good portion of it. So once that section was replaced, it was in service for quite a while and then it basically became, like anything in the canyon, it became a part of the canyon.

And the canyon will do what the canyon wants to do, rockslides, floods, high temperatures. So it became really a function of the environment it was in. And so every time you have a large winter event or even a large monsoonal rain, we have mudslides, rockslides in the canyon, and that’s just a natural part of the canyon.

And sometimes it’s hard to predict where those are going to happen. Actually we can’t predict where those are going to happen, and they sometimes happen in the most opportune places.

DK: Rob is not sure exactly how much has been spent on repairs over the years, but it’s definitely in the millions. There was a pipeline break on the North Rim just this spring that cost well over a half a million to repair.

RP: So the North Rim, because of the heavy snowfall over this last winter, record snowfall, there was a landslide after the snowmelt started that started from the North Rim and basically took out two to three hundred yards of the pipeline, so instead of actually breaking the pipeline, it completely wiped it out.

DK: Many pipeline breaks can cost from $85 to $100 thousand to repair. The cost can vary greatly depending on whether the break can be fixed in-house or if they have to hire a contractor, like they did with that North Rim break.

RP: But it also depends on where the break is. If it’s someplace where our crews can hike in and they can easily asses where the break is and they can have access to it and do the work safely, or is it in a location where they have to go from the top and they’re repelling down and they’re hanging off of long lines, repelled down to where the break is or if we have to helicopter in the crew and materials. Obviously helicopter costs play into that. So it varies. It can be as simple as a few thousand dollars to several hundred thousand dollars depending on the location.

DK: Whether or not they can give people water is secondary to a more important factor — fire suppression. Last fall while fixing a pipeline break, they were about 2 hours away from closing the park because they got down to within inches of critical volume for fire suppression.

But as Rob explained all this to me over Zoom, something strange happened.

RP: So we always keep enough in reserve for structural and wildlife fire fighting. So that’s really what the tripping point is for us; it’s the fire reserve on our water capacity, not whether or not we can fill water bottles.

Sound of the fire alarm

DK: I’m distracted cause the fire alarm is going off in my work

RP: I jinxed us

DK: Sorry, I guess I have to leave the building, but thank you.

Fade out fire alarm

DK: Well, since Rob somehow made the fire alarm in my newsroom go off to get out of the interview, I decided I better just take a trip down to the Grand Canyon to see for myself.

Sounds of getting into the car and starting the engine and road trip music coming on.

Danyelle Khmara at the Grand Canyon, during a reporting trip on the Transcanyon Waterline.

Danyelle Khmara at the Grand Canyon, during a reporting trip on the Transcanyon Waterline.

DK: I arrived at the Grand Canyon’s Shrine of the Ages building, about a 10-minute walk from the South Rim, in time for a town hall about the waterline construction.

Sounds of the meeting

RP: “The Transcanyon Waterline. We awarded the contract in March. Some of the things that you are going to see in community, again, increased construction traffic. More importantly, more helicopter activity in and around the South Rim and then down in the inner canyon. And then the other thing we’re really here to talk about today. We’ll talk about area trail closures … Fade out

DK: The new pipeline will change the water source for the South Rim from Roaring Springs to Bright Angel Creek, near Phantom Ranch, which will reduce the length of the pipeline and remove the need for a portion that experiences frequent failures.

Construction started earlier this year and is planned to go until 2027.

The longest closure will be Plateau Point Trail, from earlier this month until March of 2025, a popular hike where there will be a keystone part of the waterline replacement work and one of the most challenging parts of the project.

There will be a number of other shorter trail and campground closures over the next two-plus years, that are mostly planned and posted on a National Park web page created for the project.

There’s a couple dozen people at each of the town halls. One that night, another the next morning. And many of them work in the canyon.

VIEW LARGER Recent photos of breaks and repairs in the Transcanyon Pipeline within Grand Canyon National Park.

VIEW LARGER Recent photos of breaks and repairs in the Transcanyon Pipeline within Grand Canyon National Park. At the meeting —

Tex: It looked like that started in mid-October, but the trail closure for the Bright Angel is not until Dec. 1. I work with the mules and I’m concerned about helicopter flights around the Havasupai Gardens areas, between mid-October to Dec. 1. Is that going to impact our safety because we’re going to have helicopters flying overhead.

RP: We know when the flights are coming in … Fade out

DK: Tex is a mule wrangler. She takes groups of people down to Phantom Ranch on mule back. She’s worried that the extra helicopter noise will spook the mules, but more importantly, she’s worried with trail closures, whether she’ll have a job.

Another attendant is worried about how staff are supposed to keep people off the popular trail during closures.

At the meeting —

RP: We are going to have to be the ones to enforce the closures.

Attendant: I guess that’s the real question. As far as who’s standing out in the snow at Plateau Point guiding backpackers through at Christmas. That’s the question.

RP: And that’s one of the ones we’ll have to discuss internally.

Fade out

DK: There are definitely still a few kinks to work out, but the reality is there is really no previous blueprint for this project, with all its complexities and moving parts.

At the meeting —

Chris Carpenter: The reality of it is that the complexity of the undertaking in terms of this construction is unprecedented, so we fully expect to run into situations that are unplanned.

DP:: Chris Carpenter works for the National Park Service and is the portfolio manager for the project. I asked him after the meeting to elaborate on what made the project so unprecedented.

CC:: So a lot of the codes and regulations that govern engineering of water systems or just infrastructure are really based for more municipalities, flat land type of engineering. They’re not designed for miles of different topography like this system is and designed to be installed not into a canyon wall. And so the pressures in this system well exceed most other systems. In Phantom Ranch, at the lowest point, down by the Colorado River, we see 700 to 715 PSI, so pressure, which is extremely high. Most domestic pressures are somewhere around 60 to 70 PSI. So pretty dangerous stuff if not managed carefully.”

Chatter in the background… Fade out

DK: I mistakenly asked Chris for details about how they choose the size of pipe for the project. Much of the existing pipe is 6 inches in diameter, and knowing nothing about pipes, I decided in my head that that sounded small. He told me there was a mix of different sizes in the system to balance the flows and the pressures.

CC:: We actually do a water model. And we build a model and we can change the sizes of the pipe and the material to see how that behaves hydraulically. So when Rob was talking about the different reaches in there and the bypasses, all those have a model, and we have to run that model to determine what size to do all those bypasses so we don’t create unintended pressures in the rest of the system that can cause failures during construction.

DK: All right. Thank you, I appreciate it.

CC:: I give you the weedy answer on that one, so …

DK: I only understood a couple words of what you said, but I appreciate it.

CC:: OK, you bet.

Both laugh. Fade out.

DK: Despite evidence to the contrary, Chris says the engineering component was actually the simple part of the project. What makes it so complicated is the water pressure, like he just said, and the logistics of building inside the Grand Canyon.

CC:: Building it with helicopters and figuring out then, OK, here’s how we engineer. How do we then get all these materials and equipment to each of these different stage areas and build it in these phases? So, a big part of this project — we call it infrastructure project but it’s also a helicopter project. It’s just unprecedented. There’s not any other system I know of that’s so dramatic in its complexity of the hydraulics and pressures, but also the challenges of logistics and communication.

DK: Which is part of why it took so long to get the project going, on top of having the resources and mitigating impacts to visitors.

Despite previously magically making the fire alarm go off in the AZPM newsroom to get out of an interview, Rob Parrish was nice enough to take me out to the construction sites.

Recent photos of breaks and repairs in the Transcanyon Pipeline within Grand Canyon National Park.

Recent photos of breaks and repairs in the Transcanyon Pipeline within Grand Canyon National Park.Sounds of construction

DK: I really wanted to see people repelling off the cliff side and grabbing materials dangling from helicopters, but I had no such luck. The cliff side work hadn’t begun yet, so I put on a bright orange vest and a hard hat and went out to where crews are building a water treatment plant and two additional 1 million gallon tanks to store raw water next to where all the potable water for the South Rim is stored — 13-and-a-half-million gallons.

So instead of treating the water in the canyon at Roaring Springs with just chlorination, they’ll be pumping raw water up here and using a filtering process that includes micro, nano and ultrafiltration, and a bunch of other fancy-sounding processes that Rob calls “a 100-year leap forward in water treatment technology.

They’re also building a smaller water treatment plant at Phantom Ranch for use there, the guest ranch at the bottom of the canyon, less than half a mile from the banks of the Colorado River. And eventually, they are building another treatment plant for the North Rim.

About a third of the 208 million dollar construction contract for the project — 70 million — is coming from Congress and the other two-thirds is paid for by visitor fees.

When the pipe was first put in, it was said to have a lifespan of 30 years. Again, knowing nothing about pipes, I thought that sounded short. So I asked Rob why it wasn’t built to last longer.

RP: The biggest reason for the choice in design back in the 70s, with the aluminum piping, really had to do with constructibility. With the helicopter technology back then, the ability to get the materials in when they built it, it really was kind of a balance between being able to build it for durability but then also being able to build it just being able to build it in the canyon. They chose materials and locations that were easier for construction back then. There was a combination of steel pipe that was added after the fact. There’s aluminum pipe. So we’ve got a combination of various different pipe types and sizes.

DK: One issue now with the old aluminum pipe is, unlike most pipe that’s buried, it’s exposed to the elements. The aluminum gets hot, especially exposed to inner canyon temperatures, which can hit triple-digits in the summer, and it has cold water going through it, which adds a lot of stress on the system.

As part of the new system, there will be a lot of places where the pipe is buried and/or encased in steel, which will make it less susceptible to environmental extremes.

DK: So, do you have a sense of how often breaks will happen with the new system?

RP: I’m not going to jinx myself and say never. The canyon being what the canyon is, and the canyon will take with the canyon wants, I imagine we will have some breaks. Fade out

DK: Typically when there’s a break, water use can continue as normal for a while due to the millions of gallons stored.

As they get closer to reaching that tipping point for the fire suppression stores, they may need to go into water restrictions, which means all the restaurants and concessions in the park will switch to paper and plastic eating utensils.

I went to talk to some of the food services workers about what it’s like when they’re in water conservation measures. Most of them said it doesn’t change their job much but does add a huge expense to the business for the cost of disposable plates and utensils.

Most of the people I talked to were terrified of the microphone and recorder I was carrying, except one lady working as a hostess in a dining hall by the South Rim.

Sounds of the dinning hall

DK: Do you guys have to go to paper plates and stuff like that?

Hostess: We do, yeah.

DK: How often does that happen?

Hostess: It depends on what stage we’re at. If it’s a stage two, that’s one of the things we have to do. We did that for about three weeks. However long that was implemented, two or three weeks.

DK: Does it make a difference in your work?

Hostess: It’s kind of the same. It doesn’t change anything for me. But for our dishwashers and people like that, yeah.

DK: Do dishwashers still come to work when there’s no dishes being washed?

Hostess: Oh, they sure do because there’s still dishes that have to be washed, like everything that we use for breakfast and dinner. That still has to be washed.

Fade out

DK: And if the water levels get even closer to what they need for fire suppression, they consider closing the park.

VIEW LARGER Recent photos of breaks and repairs in the Transcanyon Pipeline within Grand Canyon National Park.

VIEW LARGER Recent photos of breaks and repairs in the Transcanyon Pipeline within Grand Canyon National Park. RP: Not this year, but last September, the break lasted several weeks, and we got to a point where if we weren’t able to start recharging the system, we were several hours away from closing the park just to maintain the fire suppression and to make sure that everybody was safe.

DK: But you haven’t had to close the park?

RP: Not in the history, no. We’ve probably come close a few times, but our facilities folks are led by a couple of wonder women and a bunch of wonder men and they really do a very good job of identifying where the breaks are, getting the pieces they need put together. They work with our aviation crews to get it helicoptered in, survey where the breaks are, and fortunately as old as this thing is, as many breaks as we have, they’re used to doing it and they know what to do and they have a pretty good system to get it in. And a lot of the real problem, the challenge, comes down to it’s not so much the repair itself, it’s the access. There are a few times where the break is in an area where they can’t physically work on the break. They have to go in first, with our trail crews, and actually maybe flatten out a part of the trail or create a safe work zone for them to work from. Or if they have to repel down, get further up the canyon and actually create anchor points for them to tie off to so they can then repel down to where the site is. And that a lot of times takes longer than the actual repair itself.

DK: That sounds like that would take a specific set of skills to be able to do that.

RP: People that are a lot more brave and more skilled than myself. Our facilities folks are really good at what they do, and they’re looking forward to not having to do those emergency repairs and actually get to a point where they can do planned maintenance on the system rather than emergency maintenance.

Sounds of getting out of a car and construction

DK: After visiting the site of the new water treatment plant, we headed just up the road to where crews were building the two new raw-water tanks.

DKe: And so all these years that there have been all these breaks and stuff, this hasn’t been something that visitors to the park have even had to be aware of, correct?

RP: To tell you the truth, I don’t think most visitors give a second thought to where the water’s coming from or how it gets there. They just know that the National Park Service is here to protect and preserve that park, and it’s something secondary that I think a lot of people, particularly when they see the South Rim, the village itself, with all the developments here, I think clean drinking water is something that I think a lot of people take for granted, Whether it’s here or the South Rim or in Tusayan or Valley or any place here in Arizona or across the Southwest or America in general, people just really don’t think about what it takes to get clean drinking water. (Construction sounds getting louder.) And it’s one of the things that we’re lucky about here in this country is it’s something that we focused on for the better part of our country, municipalities and in this case, the Park Service providing clean, potable water. (Construction sounds get really loud.)

DK: (Laughing) I think that is even too loud for my background sound.

Fade out.

DK: We went into the Grand Canyon headquarters, which are just some dimly-lit, mostly empty offices. I have a feeling people who work in the Grand Canyon spend a lot of time outdoors. I asked Rob why the pipe replacement took so long to happen, and he said a lot has changed since the pipe was built that they had to consider, like the changes in environmental stewardship. There are a lot more checks and balances now and studies needed to be done. Also, creating a modern design for the pipe in such an unprecedented place as the Grand Canyon took time.

RP: It takes time to go through the process of deciding what we’re gonna build, when we’re gonna build and how we’re gonna build it. And that process started back in 2012. So it’s really been about a 15 year journey of us going through all the environmental compliance. Making sure we’re not going to create any more damage than we need to, studying what the flows of the pipeline are and actually predicting also what our water consumption is going to be. Because it’s enough to say, ‘We’re going to provide a gallon of water today,’ but what happens if two days from now, we need to provide five gallons of water?

DK: They are shooting for this project to last 75 years. Rob says his grandkids will have to deal with fixing this one day.

The Grand Canyon, seen from the patio of Bright Angel Lodge. The El Tovar Hotel, and the more recent Kachina Lodge are visible in the image.

The Grand Canyon, seen from the patio of Bright Angel Lodge. The El Tovar Hotel, and the more recent Kachina Lodge are visible in the image.

Sounds of nature and walking

DK: So I didn’t get to see people repelling off cliffs to fix bursting water pipes, but I did walk the 10 minutes from the headquarters to the South Rim to watch the sunset.

I thought about what Rob had said about America investing in its water infrastructure, and I thought about how different the country was when the waterline was built in the 60s, by hand and with tools that were much more rudimentary than what we have today.

I got dinner at El Tovar Hotel that night, overlooking the South Rim. I ate at the bar and chatted with the bartender. He was in his 60s and had lived in the park for more than 20 years. He told me he’ll retire when they close his coffin lid.

And yes, he has been here through many water restrictions, but that’s not something he thinks about much. He’s not thinking about the upcoming trail closures or the extra helicopter noise or the likely ebb of water restrictions to come. What he thinks about are the hikes he will take on the days when he has a short shift at the bar.

From the Grand Canyon’s South Rim, I’m Danyelle Khmara.

Sounds of getting into the car and starting the engine and road trip music coming on.

Zac Ziegler: For people who visit or call Grand Canyon National Park home, the water issues mainly come around moving water up to the rim where the homes, hotels and other businesses sit.

But, head downstream to one of the most remote tribal nations in America, and the water issues are very different.

The Havasupai people's land sits in canyon, surrounded on all sides by the park. They're not worried about pumping the water up. Their worries are about what trickles down.

Upstream from them sits an area where uranium mining was once plentiful. And that atomic-age history is causing concerns about water quality.

That's next time.

Tapped is a production of AZPM News.

This episode was written, produced and mixed by Danyelle Khmara, with editing and mixing help by me, Zac Ziegler.

Our theme music is by Michael Greenwald.

Visit our website in the podcast section of azpm.org for pictures, links and more. Thanks for listening.

Music fades out

This episode of Tapped was supported by a grant from The Water Desk, an independent journalism initiative based at the University of Colorado Boulder's Center for Environmental Journalism.

By submitting your comments, you hereby give AZPM the right to post your comments and potentially use them in any other form of media operated by this institution.